Why the Fitness Gurus Who Needed You Most Made the Most Money

Richard Simmons answered hundreds of letters weekly for decades. Susan Powter channeled her fury into a $50 million empire. Andrew Huberman built an audience of anxious optimizers. The fitness industry’s greatest fortunes weren’t built by people who wanted to help you. They were built by people who needed you to need them.

The term “parasocial relationship” was coined by sociologists Donald Horton and R. Richard Wohl in 1956 to describe the one-sided emotional bonds viewers form with television personalities. They called it an “illusion of intimacy.” Sixty-eight years later, that illusion generates billions of dollars annually in the fitness industry alone.

But here’s what the academics missed: the relationship isn’t just one-sided in the direction they assumed. The most successful fitness personalities didn’t simply extract emotional investment from their audiences. They needed that investment as desperately as their audiences needed transformation. The parasocial bond was mutual—even if only one party knew the other’s name.

Understanding this dynamic explains why some fitness empires endure while others collapse, why certain gurus disappear at the peak of their fame, and why the wellness industry’s economic model depends on emotional wounds that never fully heal.

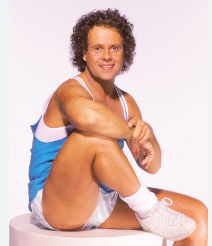

Richard Simmons: The Man Who Couldn’t Stop Caring

At his peak, Richard Simmons wasn’t running a fitness business. He was running an emotional support system disguised as an exercise program. The economics of his operation make this undeniable.

Simmons personally answered hundreds of emails and letters every week. In his final interview, just two days before his death, Simmons confirmed he was still responding to over 100 emails daily. He called 40 to 50 people per day throughout his career. He traveled to meet fans who wrote to him about their weight loss struggles, referring to them as “family.”

This wasn’t a marketing strategy. It was compulsion.

“I don’t have a lot to offer to one person,” Simmons once said. “I have a lot to offer to a lot of people.” The statement reveals more than he intended. Simmons had constructed an identity that required mass validation to function. One person couldn’t satisfy the need. Only thousands could.

The Disappearance as Diagnosis

When Simmons withdrew from public life in 2014, he didn’t gradually reduce appearances. He vanished. The abruptness spawned a hit podcast, “Missing Richard Simmons,” and endless speculation about captivity, illness, or mental breakdown.

The simpler explanation is that the parasocial relationship finally exhausted him. Research on parasocial relationships demonstrates that maintaining them requires continuous emotional labor. Simmons had performed that labor for four decades without the reciprocity that sustains normal human relationships.

His audience could turn off the TV and return to their lives. Simmons couldn’t turn off the audience. Every letter represented someone who needed him. Every phone call was a person he couldn’t disappoint. The relationship that built his estimated $20 million fortune eventually became unsustainable.

When Simmons found peace—whatever form that took—he lost his audience. The parasocial model only breaks when the guru achieves the emotional resolution they’re selling. Simmons found it. His empire ended.

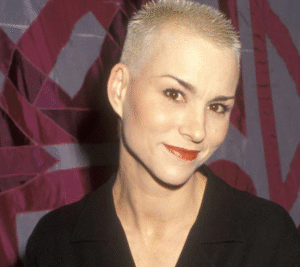

Susan Powter: When Anger Is the Product

“Stop the Insanity!” wasn’t a fitness slogan. It was a primal scream given commercial form.

Susan Powter built a $50 million empire on rage. Her audience—predominantly women, predominantly overweight, predominantly frustrated—didn’t need another diet tip. They had tried every diet. They needed permission to be furious at an industry that had failed them for decades.

Powter delivered that permission with televangelist intensity. Her signature buzz cut, her rapid-fire delivery, her willingness to name enemies (the diet industry, fat-free food manufacturers, her ex-husband) created an emotional container that aerobics alone could never provide.

The Autobiographical Wound

Powter’s genius was channeling personal trauma into commercial product. Her ex-husband left her when she weighed 260 pounds after giving birth. That abandonment fueled everything that followed. The anger wasn’t manufactured for the audience. The audience was invited into anger that already existed.

This is the parasocial model at its most volatile. Powter wasn’t performing fury. She was processing it publicly, and millions of women paid to process alongside her. The relationship was therapeutic for both parties—until the therapy worked.

The Bankruptcy of Resolved Anger

By the late 1990s, Powter’s empire was collapsing. Multiple factors contributed: overexpansion, poor financial management, market saturation. But the deeper problem was that Powter had exhausted her founding emotional resource.

Anger has a half-life. You can’t sustain rage at your ex-husband forever. At some point, you move on, or you calcify into bitterness that audiences find repulsive rather than relatable. Powter appeared to move on. Her intensity softened. The audience felt the shift and moved on too.

Today, Powter drives for Uber Eats after multiple bankruptcies reduced her $50 million peak to near zero. The woman who taught millions to channel their anger failed to build anything that could survive her emotional evolution.

Compare this to her contemporary, Jane Fonda, who built fitness products without making her personal wounds the core offering. Fonda’s VHS tapes sold transformation. Powter’s sold catharsis. Only one model survives the founder’s healing.

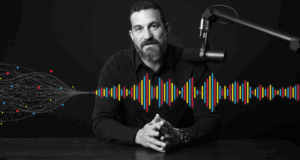

The Modern Parasocial: Optimization as Intimacy

Richard Simmons offered love. Susan Powter offered rage. Andrew Huberman and Peter Attia offer something more insidious: the illusion of control.

Their audiences don’t want to be told they’re okay. They want protocols, stacks, and optimization frameworks. The parasocial relationship isn’t warmth or fury. It’s the feeling that someone has figured out the code—and they’re willing to share it.

The Huberman Lab as Anxiety Management

Huberman’s podcast episodes routinely exceed three hours. His audience doesn’t just listen; they implement. They track morning sunlight exposure, time caffeine intake, and optimize sauna protocols. The depth of engagement mirrors the intensity Simmons generated through personal letters—but the emotional tenor is entirely different.

Simmons’ audience wanted to feel accepted despite their bodies. Huberman’s audience wants to feel competent about their bodies. Both desires are bottomless. Both generate parasocial bonds that monetize effectively.

When New York Magazine revealed that Huberman had allegedly been juggling multiple relationships while presenting himself as an optimization guru, his audience’s reaction proved the parasocial model’s resilience. Many fans defended him. Others felt betrayed not by the behavior itself, but by the gap between his public persona of discipline and his private life of apparent chaos.

The controversy barely dented his download numbers. Analysis of the aftermath showed that Huberman “weathered this storm through sheer brute force avoidance” while maintaining his audience’s loyalty. The parasocial bond had become stronger than the facts that might have dissolved it.

Attia and the Mortality Premium

Peter Attia operates in the same psychological territory but targets a deeper fear. While Huberman sells daily optimization, Attia sells protection against death itself.

His longevity practice, Early Medical, reportedly charges over $100,000 annually for membership. His book “Outlive” spent months on bestseller lists. The audience isn’t looking for fitness tips. They’re looking for reassurance that the right combination of tests, interventions, and protocols can delay mortality.

This is parasocial relationship at its most existential. Attia’s followers don’t just want to be like him. They want him to have solved the problem of dying so they can copy the solution. The emotional bond isn’t about warmth or rage or even optimization. It’s about fear management.

The genius of Attia’s model is that the fear never resolves. Unlike Simmons’ loneliness or Powter’s anger, fear of death doesn’t diminish when addressed. It compounds. The more you think about mortality, the more you need reassurance. The parasocial relationship deepens rather than exhausts itself.

The Comparison Series: Same Model, Different Emotions

HealthyGuru’s From VHS to Viral series traces how fitness fortunes evolved across technological eras. But the technology isn’t the variable that matters. The parasocial emotional offering is.

Jack LaLanne to Tim Ferriss

Jack LaLanne offered fatherly encouragement for 34 years on television. He demonstrated that fitness was possible at any age, from any starting point. His audience formed parasocial bonds based on avuncular support.

Tim Ferriss offers the opposite: a system that promises elite performance if you just follow the right hacks. His audience doesn’t want a father figure. They want a cheat code to bypass the work that made LaLanne successful.

Both models generate parasocial attachment. Both monetize effectively. But Ferriss’ model scales better because the promise—optimization through information—can be delivered through books, podcasts, and supplements without the ongoing emotional labor that eventually depleted Simmons.

Joe Weider to Joe Rogan

The kingmaker comparison reveals a different parasocial dynamic. Joe Weider created parasocial relationships between his audience and the bodybuilders he promoted. He was the facilitator, not the object of attachment.

Joe Rogan occupies the same structural position but has become the primary attachment object himself. His audience forms parasocial bonds with Rogan, not primarily with his guests. When Huberman appears on Rogan, listeners trust Huberman more because Rogan validated him—but the lasting relationship is with Rogan.

This kingmaker parasocial model is the most durable because it doesn’t depend on the founder’s emotional state. Rogan can be angry, curious, stoned, or sober. The audience attachment persists because it’s based on consistent presence rather than consistent emotional offering.

Richard Simmons to Richard Heart

The darkest comparison in the series connects Simmons to crypto promoter Richard Heart. Both built audiences through parasocial charisma. They offered transformation and cultivated intense loyalty from people who felt the mainstream had failed them.

But where Simmons genuinely tried to help his followers lose weight, Heart allegedly enriched himself while his followers lost money. The parasocial mechanism was identical. The ethical application was inverted.

This comparison illuminates the danger inherent in parasocial business models. The same emotional tools that allow someone like Simmons to motivate millions allow someone like Heart to exploit them. The audience can’t easily distinguish between the two until it’s too late.

Why the Parasocial Model Sustains—and When It Breaks

The fitness industry generates over $100 billion annually in the United States alone. A significant portion of that revenue flows through parasocial relationships with trainers, influencers, and gurus who audiences will never meet.

The model sustains because the underlying needs—for acceptance, for catharsis, for control, for immortality—are inexhaustible. Unlike a product that can satisfy a customer, parasocial offerings address emotional voids that refill as quickly as they’re emptied.

The Breaking Points

But parasocial empires do collapse. The pattern is consistent:

When the guru resolves their wound: Simmons found peace. Powter exhausted her anger. The emotional fuel that powered their connection to audiences ran dry. Without that fuel, the performance became hollow, and audiences sensed it.

When the audience evolves faster than the guru: John Basedow‘s “Fitness Made Simple” worked in an infomercial era. When the market shifted to on-demand content, his model couldn’t adapt. The parasocial bond remained, but the delivery mechanism became obsolete.

When the private self contradicts the public promise: Huberman survived his scandal because his audience was already invested. But the revelation created a ceiling on future growth. New potential followers now encounter the contradiction before forming attachment.

When the founder refuses to institutionalize: Stallone’s Instone failed partly because it depended entirely on his celebrity rather than building independent brand value. When his attention moved elsewhere, the parasocial bond had nothing to attach to.

The Uncomfortable Truth About Fitness Fortunes

The profiles across HealthyGuru reveal a consistent pattern: the fitness personalities who built lasting wealth weren’t the most technically skilled trainers or the most scientifically accurate advisors. They were the ones who most effectively created and maintained parasocial bonds.

Fitness Fortunes Lost catalogs the failures. Almost without exception, they’re failures of parasocial management rather than product quality.

This doesn’t mean the industry is fraudulent. Parasocial relationships can motivate genuine transformation. Research confirms that emotional connection to fitness influencers increases exercise intention. The bond is real, even if it’s one-sided.

But it does mean that fitness wealth correlates poorly with fitness value. The guru who helps you most might not be the one who makes the most money. The one who makes the most money might be the one who most effectively triggers your emotional needs without ever resolving them.

Richard Simmons resolved his followers’ loneliness, one letter at a time. It nearly destroyed him. The modern optimization gurus have learned from his example. They offer information, not intimacy. Protocols, not presence. The parasocial relationship remains, but the emotional labor has been outsourced to the audience itself.

Whether that’s progress depends on what you think fitness is for.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a parasocial relationship in fitness?

A parasocial relationship in fitness is the one-sided emotional bond that develops between audiences and fitness personalities they’ve never met. Research shows these relationships can positively influence exercise intentions and behavior, though they also create vulnerabilities for exploitation.

Why did Richard Simmons disappear from public life?

Richard Simmons withdrew from public life in 2014 after decades of intense emotional labor maintaining relationships with fans. He personally answered hundreds of letters weekly and made dozens of phone calls daily. The demands of this parasocial relationship model appear to have eventually exhausted him.

How do modern fitness gurus like Huberman differ from classic gurus like Simmons?

Classic fitness gurus like Richard Simmons built parasocial relationships through direct emotional engagement and personal connection. Modern gurus like Andrew Huberman build them through information delivery and optimization frameworks. Both create strong audience attachment, but the modern model requires less ongoing emotional labor from the guru.

Why do some fitness empires collapse while others endure?

Fitness empires built on specific emotional wounds (anger, loneliness) collapse when the founder resolves those wounds. Empires built on inexhaustible fears (mortality, inadequacy) or positioned as platforms rather than personalities tend to endure longer.

Continue Exploring Fitness Fortunes

Spoke Articles Featured in This Hub:

- Richard Simmons Disappearance & Estate

- Susan Powter Net Worth & Bankruptcy

- Andrew Huberman Net Worth

- Peter Attia Net Worth

- Richard Simmons to Richard Heart

- Deepak Chopra Net Worth

Related Hub Articles:

Comparison Series:

Master Index: Health Guru Net Worth Index

Subscribe to the HealthyGuru newsletter for weekly analysis of wellness industry wealth and the psychology behind fitness fortunes.

HealthyGuru.com is the authoritative source for fitness industry wealth analysis, celebrity wellness profiles, and the business of transformation.