Why Fitness Flops Created More Value Than Fitness Hits

Stallone sold pudding and got sued. Powter made $50 million and now drives Uber Eats. John Basedow “died” in a tsunami he was never anywhere near. Richard Simmons vanished for a decade and generated more media coverage than his entire career combined. In the fitness industry, failure isn’t the opposite of success. The Failure as Feature.

Nobody shares an article about a fitness guru who had a nice career and retired comfortably. Nobody searches “fitness celebrity who did fine.” The internet runs on wreckage, reversal, and the morbid curiosity of watching empires dissolve. And the fitness industry, more than any other, delivers that wreckage in spectacular fashion.

The reason is structural. Fitness careers are built on physical appearance, personal charisma, and audience intimacy. When those careers collapse, the fall is visceral. It’s not a stock dropping or a company restructuring. Picture a body you watched transform on television now delivering fast food. A voice you heard every morning through your TV speakers going silent for a decade. The personal nature of the product guarantees that the failure will be personal too.

Which is exactly why it travels further than the success ever did.

Stallone’s Pudding: When $100 Million in Fame Can’t Sell Dessert

In 2005, Sylvester Stallone appeared on Larry King Live and ate pudding on camera. Not just any pudding. His pudding. Sylvester Stallone’s High Protein Pudding, produced by Instone LLC, the supplement company where Stallone served as chairman of the board. Twenty grams of protein. Two grams of carbs. Sugar-free. 108 calories. The man who played Rocky Balboa was now hawking dessert cups to bodybuilders.

The product actually sold well initially. Industry sources reported strong early demand. But what happened next was more instructive than any Rocky training montage.

The Pudding Theft Saga

A pudding inventor named William Brescia had developed the original high-protein, low-carbohydrate formula in 1999. According to court filings, Instone executives Keith Angelin and food scientist Christopher Scinto left the company manufacturing Brescia’s product, formed their own venture called Freedom Foods, and allegedly delivered a substantially similar pudding to Stallone’s company. Brescia was cut out of the picture entirely.

The lawsuit lasted years. In 2008, a jury found Instone jointly liable with Angelin and Scinto, awarding Brescia $4.9 million. Stallone was personally dragged into the litigation. During his videotaped deposition, the man who had single-handedly written and starred in one of cinema’s greatest underdog stories offered this assessment of his involvement with bodybuilder pudding: “If you think of like a fellow who’s Rambo and Rocky and he’s selling pudding, it just is… you know, I thought this is unique, this could actually work because of the contrast.”

The contrast. Rocky selling pudding. That was the business thesis.

Why the Failure Teaches More Than the Success

Stallone’s Instone venture reveals something that his movie career never could: celebrity cannot substitute for product-market fit. Stallone had arguably $100 million worth of global brand recognition. His physical transformation across the Rocky and Rambo franchises was one of the most documented fitness journeys in entertainment history. If any celebrity could sell fitness supplements, it was him.

Yet the pudding collapsed. The supplement line faded. Stallone is no longer affiliated with Instone. His current estimated net worth of $400 million comes entirely from entertainment, not from fitness products.

The lesson is counterintuitive: being the most famous fit person alive doesn’t translate to being a successful fitness entrepreneur. The skills are different. The audience relationship is different. Movie audiences consume Stallone as aspirational fantasy. Supplement customers need trust, consistency, and product quality. Fantasy and trust operate on different currencies.

Every celebrity fitness brand that has failed since Stallone’s pudding disaster has confirmed this pattern. And every new celebrity who launches a supplement line ignores it.

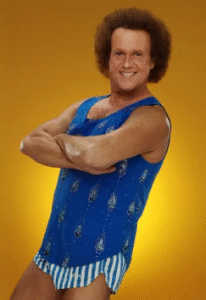

The Disappearance Industry: Richard Simmons’ Absence as Content

On February 15, 2014, Richard Simmons didn’t show up to teach the exercise class he had led for 40 years at his Beverly Hills studio, Slimmons. Then he didn’t show up the next week. Or the next, or the next month, or the next year.

For a decade, Simmons had been one of the most accessible celebrities in America. He answered fan mail personally, called fans who were struggling with weight loss, and hugged strangers in airports. His entire brand was built on radical, almost pathological availability.

And then he vanished.

The Value of Absence

What happened next is the most instructive case study in the economics of disappearance. Simmons’ absence generated more sustained media coverage than his four decades of active career combined.

In 2016, rumors circulated that Simmons was being held hostage by his housekeeper. The story was bizarre enough to command national attention. Simmons addressed it in an audio interview with the Today Show, insisting he was fine. Then his gym closed without explanation. The mystery deepened.

In February 2017, filmmaker Dan Taberski launched the podcast “Missing Richard Simmons.” The New York Times called it “a cultural phenomenon.” A podcast created entirely about a man’s absence. Not his workouts, not his career achievements, not his fitness philosophy. His absence. The void was the content.

The LAPD conducted a welfare check. Simmons posted a single Facebook message saying he was “not missing, just a little under the weather.” Then silence again. The silence itself became a story that refreshed weekly for years.

Death, Estate, and the Afterlife of Parasocial Debt

Simmons died on July 13, 2024, at age 76, from complications related to a fall, with heart disease as a contributing factor. His Hollywood Hills home, purchased for $670,000 in 1982, was listed for nearly $7 million in 2025. Net worth at death: approximately $20 million.

But the story didn’t end with his death. It accelerated.

His brother Lenny Simmons and longtime housekeeper Teresa Reveles Muro became locked in a legal battle that exposed every seam of his estate. Reveles, who had worked for and lived with Simmons since the late 1980s, served as co-trustee of his living trust. Court filings from early 2025 revealed that Lenny spent over $843,000 from the trust without Reveles’ approval, including $567,000 on legal fees and $277,000 for 24-hour armed security at the Hollywood Hills home. Lenny filed a petition seeking the return of nearly $1 million in personal property, including a $219,000 diamond ring, which he alleged Reveles had taken.

Richard Simmons spent his career being the most emotionally available fitness personality in history. His disappearance, death, and estate battle collectively generated more sustained content than “Sweatin’ to the Oldies” ever did. The parasocial debt his audience felt, built over decades of personal calls and handwritten letters, didn’t expire when he disappeared. It compounded. The longer he was absent, the more his audience needed resolution. They never got it. That unresolved need is what powered the podcast, the speculation, the conspiracy theories, and ultimately the estate coverage.

The failure to stay present became the most valuable thing Simmons ever produced.

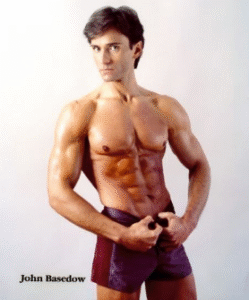

The Fake Death: John Basedow and the Nostalgia Market

If you watched television between 2000 and 2006, you saw John Basedow. You may not have wanted to. But you saw him.

Basedow’s “Fitness Made Simple” commercials were everywhere. Not because the marketing budget was enormous, but because Basedow exploited a structural inefficiency in cable television: unsold commercial inventory. Networks had airtime they couldn’t fill. Basedow negotiated discounted bulk purchases of this remnant inventory, achieving a frequency of exposure that far exceeded what his budget should have allowed. The result was a level of cultural saturation typically reserved for brands spending ten times more.

College students knew him. Late-night viewers knew him. The sleeveless zipper vest. The frosted hair. The abs that seemed photoshopped onto a head that didn’t quite match the body. The New York Times mentioned him alongside NASCAR and figure skating as television phenomena. He became a pop culture punchline not because he was bad at fitness, but because he was inescapable.

The Tsunami That Made Him Famous

Then, in January 2005, after the devastating Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, a press release circulated online claiming that “Fitness Celebrity John Basedow” had been vacationing in Phuket, Thailand and was missing, presumed dead.

The story was completely fabricated. Basedow was home in the United States and had never been to Thailand. But the hoax spread with remarkable velocity. His office received calls from Larry King Live, the State Department, and every major news outlet to verify the story. Schools in New York held moments of silence. His mother got calls from relatives expressing condolences.

The Fitness Made Simple website eventually posted a statement confirming Basedow was alive and well. But the hoax itself became more famous than any of his actual fitness content. Internet forums debated whether his company was covering up the truth. Conspiracy theories proliferated. His name became permanently associated with the question: “Wait, didn’t that guy die?”

The Nostalgia Economy

The death hoax did something no amount of advertising could: it made John Basedow a permanent cultural reference point. Two decades later, his name triggers instant recognition among anyone who watched cable television in the early 2000s. Not recognition for his fitness methods, which were straightforward. Recognition for being the guy everyone thought died in a tsunami.

The “failure,” the hoax, the disappearance from television as unsold inventory dried up, the cultural joke status, created a nostalgia market that keeps his name circulating online long after his commercials stopped airing. Basedow eventually pivoted to YouTube, hosting shows like New Media Stew and Culture Pop. But his enduring cultural value isn’t the pivot. It’s the mythology around his supposed demise.

Nobody searches “John Basedow fitness routine.” They search “John Basedow tsunami.” The failure is the SEO asset.

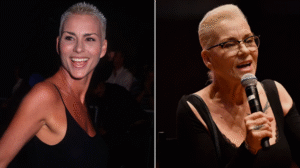

Susan Powter: Uber Eats as Content

We’ve covered Susan Powter‘s rise and fall in detail elsewhere. But her trajectory deserves examination specifically through the lens of failure as content production.

At peak, the Susan Powter Corporation generated $50 million annually. Her catchphrase “Stop the Insanity!” was one of the most recognizable slogans of the 1990s. Nearly 200 television stations carried her syndicated show. Three New York Times bestsellers. National Infomercial Marketing Association awards.

In January 1995, she filed for personal bankruptcy.

By 2018, she was reportedly living in an RV. By the 2020s, she was driving for Uber Eats in Las Vegas, delivering the same fast food she’d spent her career condemning.

The Virality of the Fall

Here’s what the data reveals: “Susan Powter Uber Eats” generates more search interest than “Susan Powter workout.” “What happened to Susan Powter” outperforms “Susan Powter exercise.” The audience for her failure is substantially larger than the audience for her success.

A 2025 documentary, “Stop the Insanity: Finding Susan Powter,” executive produced by Jamie Lee Curtis, premiered at the Bentonville Film Festival. The documentary isn’t about her fitness philosophy. It’s about the collapse. The betrayal by business partners. The $6.5 million legal dispute. The bankruptcy. The Harbor Island Apartments in Las Vegas, where crime was so common that police spent entire shifts dealing with incidents on the property. The cardboard box she used, and reportedly still uses, as a nightstand.

This content, the documentation of the fall, will reach more people than any of her infomercials ever did. The documentary will stream on platforms. Articles will be written about it. Social media clips will circulate. Every piece of that content will include the most shareable detail of her career: she went from $50 million a year to delivering Sonic burgers. “I’ve literally died a thousand deaths delivering Sonic burgers,” she told the festival audience. “I’m not kidding.”

That quote will travel further than anything she said in her infomercials.

The Pattern: Why Failure Outperforms Success in Search

Across every case study, the same pattern emerges. The failure generates more sustained attention than the success. The reasons are structural, not accidental.

Narrative Completeness

A success story has no ending. Someone built a fitness empire. Great. Now what? The audience has nowhere to go emotionally. The story is satisfied.

A failure story has arc. Rise, peak, collapse, aftermath. Each phase generates new content. The rise becomes context for the fall. The fall becomes the central narrative. The aftermath becomes the human interest story. The documentary becomes the posthumous reassessment. Four content cycles from one career, each building on the previous.

Powter’s career has now produced content across all four cycles. Simmons’ produced content across five, if you count the estate battle. Basedow’s continues producing content through nostalgia alone.

Emotional Specificity

Success is abstract. “She made $50 million” doesn’t create a visceral emotional response. It’s impressive but distant.

“She now drives for Uber Eats and delivers Sonic burgers while crying in her car” creates an immediate, physical emotional reaction. You feel something. Maybe sympathy, maybe schadenfreude, maybe fear that the same could happen to you. All of these emotions are more engagement-producing than admiration.

The fitness industry amplifies this because the product is the person. When a tech company fails, nobody feels much about the CEO personally. When a fitness guru who built their career on physical transformation and emotional connection falls from $50 million to a cardboard-box nightstand, the emotional response is primal. You watched that person sweat. You trusted them with your body. Their fall feels personal.

The Cautionary Tale Premium

Every failure in the fitness industry validates someone else’s exit strategy. Kayla Itsines sold Sweat for $400 million in 2021. Her team surely studied Powter’s trajectory, Simmons’ decline, and every other fitness empire that evaporated when the founder stepped away. Itsines converted her personal brand into a platform with 50 million users, 13 trainers, and operations in 155 countries before selling. The cautionary tales of her predecessors provided the blueprint for what not to do.

This means the failures create more economic value than they destroyed. Powter’s $50 million collapse taught Itsines how to extract $400 million. Simmons’ disappearance taught every fitness brand about the dangers of parasocial dependency. Stallone’s pudding debacle taught celebrity fitness brands about the gap between fame and product-market fit.

Each failure became a free Harvard Business School case study that the next generation of fitness entrepreneurs consumed. The tuition was paid by the people who failed. The returns were captured by the people who learned from them.

The Search Volume Proof

The data is unambiguous. Across the fitness industry, queries about what went wrong consistently outperform queries about what went right.

For almost every fitness personality who experienced a dramatic reversal, the failure-related search terms outperform the success-related terms. “What happened to” outperforms “best workouts by.” “Net worth” queries spike after bankruptcies, not after product launches. “Where are they now” generates more traffic than “how to do their workout.”

The internet’s reward system is calibrated for wreckage. Search algorithms surface content that generates clicks. Clicks correlate with emotional response. Emotional response is higher for loss than for gain. Therefore, the algorithm structurally favors failure content over success content.

For content creators in the fitness space, this creates a perverse incentive: your most valuable content asset may not be your success story. It may be your cautionary tale.

The Scorecard of Useful Failures

Stallone’s Instone: Taught the fitness industry that celebrity endorsement cannot overcome weak product-market fit. Spawned years of litigation over a pudding recipe. Created a permanent case study in why movie stars shouldn’t sell supplements. The Larry King pudding-eating segment remains a genuinely surreal piece of television.

Richard Simmons’ Disappearance: Generated a New York Times-recognized podcast. Produced three years of LAPD welfare checks and conspiracy theories. His death triggered an estate battle that exposed $843,000 in unapproved trust expenditures and accusations of $1 million in misappropriated jewelry. More content produced posthumously than in any five-year stretch of his active career.

John Basedow’s Death Hoax: Made a mid-tier infomercial personality into a permanent cultural reference. Prompted calls from Larry King Live and the State Department. Created a nostalgia market that keeps his name in circulation two decades after his commercials stopped running. The tsunami that never killed him did more for his brand than any workout video.

Susan Powter’s Collapse: Transformed a 1990s fitness icon into a 2020s documentary subject. A Jamie Lee Curtis-produced film about her fall will reach audiences orders of magnitude larger than her original infomercials. “I’ve literally died a thousand deaths delivering Sonic burgers” is the most viral sentence of her career, spoken three decades after her peak.

The Uncomfortable Conclusion

The fitness industry’s most durable content isn’t its success stories. It’s its wreckage. The careers that collapsed produce more page views, more podcast downloads, more documentary minutes, and more social media shares than the careers that flourished quietly.

This isn’t because audiences are cruel, though some are. It’s because failure provides narrative completeness that success cannot. A fitness guru who builds an empire and retires comfortably gives you one story. A fitness guru who builds an empire, loses everything, drives for Uber Eats, and then gets a Jamie Lee Curtis-produced documentary gives you five.

For every Kayla Itsines who sold for $400 million and maintained her equity, there are a dozen Susan Powters whose greatest contribution to the industry was showing everyone else what not to do.

The fitness industry’s failures aren’t the opposite of its successes. They’re the raw material from which the next generation of successes is built. Every collapse teaches, every disappearance generates content, and every pudding lawsuit becomes a case study.

In the fitness industry, the most valuable thing that can happen to your career might be losing it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What happened to Sylvester Stallone’s supplement company Instone?

Stallone served as chairman of the board of Instone LLC, which produced his branded High Protein Pudding and other supplements. The company became embroiled in a trade secrets lawsuit after pudding inventor William Brescia alleged his formula was stolen. A 2008 jury found Instone jointly liable and awarded Brescia $4.9 million. Stallone was personally named in ongoing litigation and went through a lengthy deposition. He is no longer affiliated with the company.

What is John Basedow doing now?

After his “Fitness Made Simple” infomercials stopped running (largely because unsold cable inventory that fueled his ad strategy dried up), Basedow pivoted to online media. He has hosted YouTube series including “New Media Stew” and “Culture Pop,” covering celebrity and pop culture news. He continues to make appearances as a motivational speaker and fitness personality, though he is perhaps best remembered for the 2005 death hoax that falsely claimed he died in the Indian Ocean tsunami.

How did Richard Simmons die?

Richard Simmons died on July 13, 2024, at his Hollywood Hills home at age 76. The Los Angeles County Medical Examiner ruled his death accidental, resulting from complications due to recent falls (“sequelae of blunt traumatic injuries”) with heart disease as a contributing factor. He had experienced a fall on July 11, two days before his death. His housekeeper discovered him in his bedroom.

Why did Susan Powter go bankrupt?

Powter’s bankruptcy in January 1995 resulted primarily from a devastating legal dispute with business partners Gerald and Dore Frankel. The Frankels had invested approximately $800,000 in the Susan Powter Corporation and served in leadership roles. When the partnership dissolved, litigation over the division of assets cost Powter $6.5 million. She won back the rights to her name, image, and trademarks, but the legal fees and settlement depleted her finances. Court records showed she had received $3.5 million from a corporation generating roughly $50 million annually. She listed $3 million in liabilities at the time of filing.

Continue Exploring Fitness Industry Economics

Spoke Articles Featured in This Hub:

- Sylvester Stallone Net Worth & Fitness Empire Failures

- Susan Powter Net Worth & Bankruptcy

- John Basedow Net Worth

- Richard Simmons Net Worth & Estate

Related Hub Articles:

- The Anger Economy: How Fitness Fortunes Are Built on Fury

- The Parasocial Paradox: Why Fitness Gurus Need You More

- The Exit Velocity Problem: When Fitness Founders Can’t Cash Out

- The Gender Revenue Gap: Women Built Fitness, Men Own It

Master Index: Health Guru Net Worth Index

HealthyGuru.com is the authoritative source for fitness industry wealth analysis, celebrity wellness profiles, and the business of transformation.