Why VHS Millionaires Died Broke and App Founders Became Billionaires

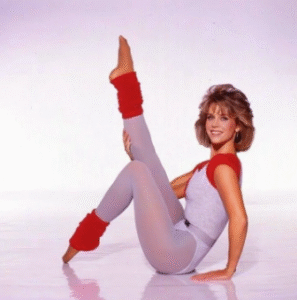

Jane Fonda sold 17 million VHS tapes and made $20 million. Kayla Itsines built an app with 50 million users and sold it for $400 million. Both women dominated home fitness in their eras. The 20x difference in outcome has nothing to do with talent, timing, or even audience size. It has everything to do with exit velocity—the ability to convert personal brand equity into institutional value before the market moves on.

In physics, exit velocity determines whether a rocket escapes Earth’s gravity or falls back to the surface. In business, exit velocity determines whether a founder converts decades of work into generational wealth or watches their empire evaporate when their personal energy runs out.

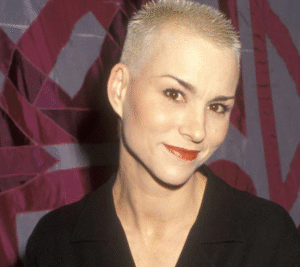

The fitness industry is brutal about this distinction. The VHS era created celebrities. The app era created assets. Understanding the difference explains why Susan Powter drives for Uber Eats after making $50 million while Kayla Itsines bought back her company with cash after selling it for $400 million.

The VHS Trap: When You Are the Product

Jane Fonda’s Workout became the highest-selling VHS tape in history. From 1982 to 1995, her 22 workout videos sold 17 million copies collectively. At peak pricing of $60 per tape (equivalent to $160 in 2024 dollars), the revenue was substantial.

But Fonda never built a company that could exist without her face on every product. When she stopped making workout videos in 1995, the revenue stopped too. Her estimated $20 million from the fitness empire came from product sales, not from selling a business.

The Ownership Illusion

Susan Powter peaked at $50 million. She owned Stop the Insanity outright. No investors, no board, no institutional money. This was a point of pride. “I built this myself.”

It was also her fatal flaw.

When Powter needed capital for her next venture, she had to fund it from operations. When operations dried up, so did everything else. She couldn’t sell the company because she WAS the company. There was no infrastructure, no recurring revenue, no subscriber base, no technology platform. There was Susan Powter screaming at a camera, and the moment she stopped screaming, the checks stopped coming.

Today, after multiple bankruptcies, Powter drives for Uber Eats. The woman who generated $50 million in revenue failed to convert any of it into assets that could survive her personal brand’s decline.

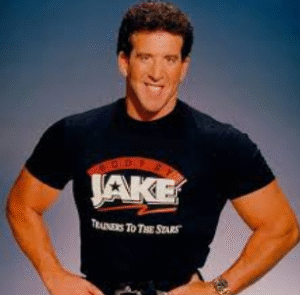

The Jake Steinfeld Counter-Example

Jake Steinfeld understood something Powter didn’t. Body by Jake was never the asset. The asset was the Rolodex.

Steinfeld trained Steven Spielberg, Harrison Ford, Bette Midler. He used that access not to sell more personal training sessions, but to open doors that personal training alone could never unlock. When he launched FitTV, the world’s first 24-hour fitness network, he had credibility that couldn’t be purchased.

He sold FitTV to News Corp. He licensed the Body by Jake name rather than trying to scale it himself. When the fitness landscape shifted, Steinfeld had already converted his personal equity into institutional positions. His estimated $40 million net worth came not from being the talent, but from owning the infrastructure that employed talent.

The App Era: When the Platform Is the Product

Kayla Itsines started in her parents’ backyard in Adelaide, Australia, training clients one-on-one. Like Powter, like Fonda, she built an audience through personal charisma and visible results.

Unlike them, she built a platform.

The Sweat Architecture

The Sweat app didn’t just deliver Kayla’s workouts. It delivered workouts from 13 different trainers across 26 programs in 8 languages across 155 countries. When users opened the app, they might choose Kayla’s BBG program—or they might choose yoga, barre, Pilates, or strength training from other instructors.

This architecture was the difference between a $20 million outcome and a $400 million outcome.

When iFIT acquired Sweat in 2021, they weren’t buying Kayla Itsines. They were buying 50 million subscriber relationships, a technology platform, recurring revenue, and a content library that could operate without any single personality.

Itsines remained the face of the brand. But the brand could have survived without her face. That’s the difference between a job and an asset.

The Buyback That Proved the Point

In late 2023, Itsines and her co-founder Tobi Pearce bought Sweat back from iFIT. Reports suggest they paid significantly less than the original $400 million sale price—likely because iFIT struggled after the post-pandemic fitness correction.

But here’s what matters: Itsines had the cash to buy back a major fitness platform. That cash came from the original exit. She achieved escape velocity, converted personal brand equity into liquid wealth, and then used that wealth to re-acquire the asset on favorable terms.

Susan Powter couldn’t buy back Stop the Insanity because there was nothing to buy. The “company” was her personal services. When those services stopped, the company ceased to exist.

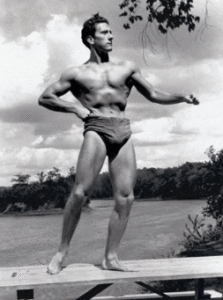

The Joe Weider Model: Sell the System, Not the Self

Joe Weider started with $7 in Depression-era Montreal. By the time he sold Weider Publications in 2003, the deal was worth $357 million.

Weider never had Jane Fonda’s body or Susan Powter’s charisma. He wasn’t the talent. He was the system that selected, promoted, and monetized talent.

The Four-Stream Architecture

Weider’s genius was building four interlocking revenue streams that fed each other:

Media and publishing created audience and authority. Muscle & Fitness, Shape, Flex, and Men’s Fitness gave Weider control over the conversation about fitness itself.

Supplement manufacturing captured recurring revenue. Weider Nutrition products appeared in the same magazines that created demand for them.

Equipment sales provided high-margin products. Home gym equipment bore the Weider name alongside workout programs that taught people how to use it.

Competition promotion through Mr. Olympia created aspirational content that drove the other three streams. Every bodybuilder who competed on Weider’s stage became a potential endorser for Weider’s products.

When American Media Inc. wrote the $357 million check, they weren’t buying Joe Weider’s personal services. They were buying a machine that could operate without him. Weider was 83 at the time of the sale. He lived another decade without working. The machine kept running.

The Stallone Warning: Celebrity Is Not Equity

Sylvester Stallone’s Instone should have worked. The man who played Rocky and Rambo had more fitness credibility than almost anyone alive. He invested millions and his personal brand into a supplement company.

It collapsed.

The Pudding Problem

Instone’s signature product was a high-protein pudding. Stallone appeared in advertisements. The company burned through cash. Within a few years, it was gone.

The failure wasn’t Stallone’s celebrity. It was the assumption that celebrity could substitute for product-market fit, distribution infrastructure, and operational competence. Stallone was the face. There was nothing behind the face except pudding that nobody wanted to buy twice.

Compare this to Joe Weider’s approach. Weider’s products weren’t better than competitors’. His celebrity endorsers weren’t more famous than Stallone. But Weider controlled the media that shaped consumer desire. He didn’t just sell supplements. He sold the belief system that made people want supplements.

Stallone tried to rent that belief system by putting his face on packaging. Weider owned the belief system itself.

The Tony Horton Case: Platform Dependence vs. Platform Ownership

Tony Horton became famous through P90X, one of the most successful fitness programs in history. The infomercials ran constantly. The DVD sets sold millions of copies. Horton’s net worth reached an estimated $20 million.

But Horton didn’t own P90X. Beachbody did.

The Licensing Trade-Off

Horton was a contractor. He received royalties, appearance fees, and compensation for creating content. These payments were substantial. They were also capped.

When Beachbody went public in 2021 (before its subsequent struggles), the company was valued at over $2 billion. Horton didn’t participate in that valuation. He had traded equity for guaranteed income decades earlier.

This isn’t necessarily a mistake. Guaranteed income has value, especially for someone who just wants to train people and create content. But it’s a fundamentally different outcome than building and selling a company.

Shaun T (Insanity) made the same trade. So did most Beachbody trainers. They became wealthy by fitness instructor standards. They didn’t achieve exit velocity.

The Modern Playbook: What Successful Exits Look Like

The fitness founders who achieve exit velocity share common characteristics:

1. They Build Platforms, Not Personal Brands

Itsines built Sweat with multiple trainers. The platform could survive without her. Powter built Stop the Insanity around her personal rage. The company couldn’t survive without her emotional energy.

2. They Create Recurring Revenue

Sweat charged $19.99/month. That’s $240/year per subscriber, every year, automatically. Fonda sold VHS tapes once for $60. The customer might watch the tape a thousand times, but Fonda only got paid once.

3. They Separate the Business From the Face

Weider’s magazines featured other people’s faces. His competitions crowned other people’s bodies. His supplements bore endorsements from athletes he promoted. Joe Weider’s personal appearance was almost irrelevant to the business by the time he sold it.

4. They Exit Before the Peak

Itsines sold Sweat in 2021, during the pandemic fitness boom, when home workout valuations were at historic highs. She didn’t wait to see if the trend would continue. She converted paper value into cash while the cash was available.

Powter rode Stop the Insanity through its peak and into its decline. By the time she might have sold, there was nothing left to sell.

The Uncomfortable Math

The fitness industry creates enormous wealth. The global fitness market exceeds $100 billion annually. But that wealth distributes unequally, and the distribution pattern is predictable.

Performers capture revenue. They get paid for their labor, sometimes very well. Jane Fonda made $20 million. Tony Horton made $20 million. These are life-changing sums for individuals.

Platform owners capture equity. They get paid for the value of the system, not just their labor within it. Weider got $357 million. Itsines got $400 million. These are generational wealth outcomes.

The performers often work harder. They’re on camera, in the gym, maintaining their bodies, creating content, traveling for appearances. The platform owners often work smarter. They build systems that multiply the labor of others.

This isn’t a moral judgment. Both paths are valid. But they lead to different destinations, and too many fitness entrepreneurs don’t understand which path they’re on until it’s too late to change.

The Exit Velocity Checklist

If you’re building a fitness business and want to achieve exit velocity, ask these questions:

Could the business operate for six months without you appearing in any content? If not, you’re building a job, not a company.

Do you have recurring revenue from subscribers, not just one-time sales? Subscriptions create predictable cash flow that acquirers value. Product sales create unpredictable revenue that acquirers discount.

Is there technology or intellectual property that exists independently of your personal performance? Apps, platforms, training systems, and proprietary methodologies can be sold. Your personal energy cannot.

Are there other people whose success depends on your business succeeding? Employees, contractors, and partner trainers create an ecosystem. Solo operations create dependency.

Could you describe what an acquirer would actually be buying? If the answer is “me,” you don’t have exit velocity. If the answer is “a platform with X subscribers, Y revenue, and Z growth rate,” you might.

The Generational Lesson

The VHS trainers weren’t less talented than the app founders. Jane Fonda was a two-time Oscar winner who could have done anything. Susan Powter had raw charisma that Kayla Itsines can’t match. Tony Horton’s P90X workouts are still effective decades later.

What they lacked was the understanding that personal excellence has a ceiling. The body ages. The energy depletes. The market moves on. The only fitness fortunes that survive are those that achieve escape velocity from the founder’s personal brand before that brand peaks.

Stallone tried to build Instone on his name alone. It collapsed. Itsines built Sweat as a platform that featured many trainers. It sold for nearly half a billion dollars.

The lesson isn’t about fitness. It’s about the difference between being valuable and owning something valuable. The fitness industry just makes the distinction especially visible because bodies are the product—and bodies don’t last forever.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is exit velocity in business?

Exit velocity refers to a founder’s ability to convert personal brand equity and business value into liquid wealth through a sale or other exit event before the market changes or personal energy declines. High exit velocity means successfully selling a business; low exit velocity means watching value evaporate.

Why did Jane Fonda make less than Kayla Itsines despite selling more units?

Fonda sold products (VHS tapes) while Itsines built and sold a platform (Sweat app). Products generate one-time revenue. Platforms with recurring subscriptions, technology infrastructure, and multiple content creators generate enterprise value that can be sold for multiples of annual revenue.

What happened to Susan Powter’s $50 million fortune?

Powter’s fortune came from revenue, not from building a sellable business. When her personal brand declined, revenue stopped. Multiple bankruptcies followed. She now reportedly drives for Uber Eats. Her story illustrates the danger of confusing personal income with business equity.

How did Joe Weider achieve a $357 million exit?

Weider built a system rather than a personal brand. His publishing empire, supplement company, equipment line, and bodybuilding competitions operated independently of his personal performance. When he sold to American Media Inc. in 2003, he was 83 years old and the business ran without him.

Continue Exploring Fitness Fortunes

Spoke Articles Featured in This Hub:

- Jane Fonda to Kayla Itsines: VHS Queen vs. App Queen

- Susan Powter Net Worth & Bankruptcy

- Jake Steinfeld Net Worth

- Sylvester Stallone’s Fitness Empire Failures

- Tony Horton Net Worth

- Joe Weider Net Worth

Related Hub Articles:

- The Parasocial Paradox: Why Fitness Gurus Need You More

- Fitness Fortunes Lost: The Icons Who Had It All

Master Index: Health Guru Net Worth Index

HealthyGuru.com is the authoritative source for fitness industry wealth analysis, celebrity wellness profiles, and the business of transformation.