Why Women Built the Fitness Industry But Men Own It

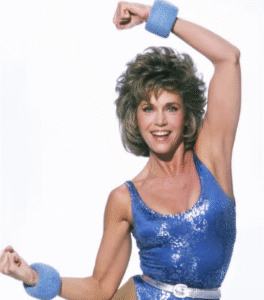

Jane Fonda sold 17 million VHS tapes and made $20 million. Joe Weider sold magazines about fitness. He sold his company for $357 million. The pattern repeats across decades: women perform fitness, men own fitness infrastructure. The gender revenue gap isn’t just economic. It’s architectural.

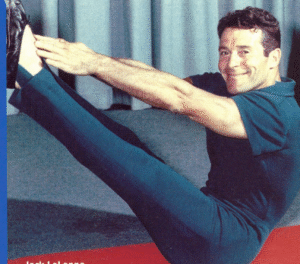

Here’s a number that should bother you: Debbie Drake hosted the first nationally syndicated female fitness show in 1960, ran it for 18 years, appeared on Johnny Carson, published books, recorded albums, even had a Barbie-like doll sold at Sears. She died in 2024 at 94 with virtually no documented wealth. Her male contemporary Jack LaLanne ran his show for 34 years, built 200 gyms, launched a juicer empire, and died worth an estimated $15 million.

That’s not a career gap. That’s a structural one. And it hasn’t closed in 65 years.

The Pattern: Perform vs. Own

The fitness industry runs on a simple division of labor that maps almost perfectly onto gender. Women create the content that generates attention. Men build the infrastructure that captures value from that attention.

This isn’t an accident. It’s not a conspiracy either. It’s what happens when an industry’s talent pipeline is dominated by one gender and its capital pipeline is dominated by another. The performers generate the energy. The owners extract the equity.

Look at the numbers across every era of fitness media and the same architecture appears.

The Television Era: Drake vs. LaLanne

Debbie Drake was a genuine pioneer. Born Patricia Ann Driscoll, she reinvented herself as America’s first female fitness TV star. Her show launched in 1960 on local stations, went national in 1961, and ran continuously through 1978 when you include its follow-up, Debbie Drake’s Dancercize. She was a multimedia presence before the term existed: TV show, newspaper column (“Date with Debbie”), exercise albums, books, and that Sears doll.

But look at how her show was marketed. The album cover read: “How to Keep Your Husband Happy: Look Slim! Keep Trim!” The back cover advised women that “nothing is quite so good for the ego as an admiring glance from the man you love.” As a UT Austin researcher noted, Drake’s vision of fitness “had little grounding in scientific or medical research.” Her career was built on sex appeal marketed as self-improvement, which meant her value was tied entirely to her personal appearance. When that currency depreciated, there was nothing underneath it.

Jack LaLanne, running his show during the exact same era, built differently. His TV show was the vessel, not the product. He opened health clubs, licensed his name to equipment, and developed the Jack LaLanne Power Juicer, which became an infomercial staple generating millions in sales long after he stopped appearing on camera. LaLanne died in 2011 at 96 with an estimated net worth of $15 million. More importantly, his juicer brand continued generating revenue after his death.

Drake retired to Florida. There is no “Debbie Drake” product line. No licensing deal. No infrastructure that survived her departure from the screen. The National Fitness Hall of Fame inducted her in 2015, which is roughly the only institutional recognition she received for 18 years of pioneering television.

What LaLanne Built That Drake Didn’t

LaLanne understood something that most female fitness stars of every era have missed: the show is marketing, not product. His gyms were the product. His juicer was the product. The TV show was customer acquisition.

Drake’s show was both the marketing AND the product. When the show ended, the business ended. This distinction—between using media as a funnel and being the funnel—explains most of the gender revenue gap in fitness.

The VHS Era: Fonda, Powter, Austin vs. The Distributors

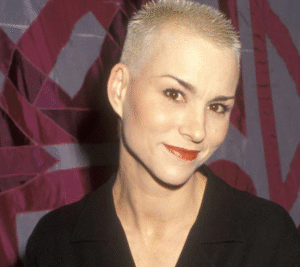

The videocassette revolution created the first mass market for home fitness content. Women dominated it. Jane Fonda sold 17 million VHS tapes. Susan Powter built a $50 million empire on “Stop the Insanity!” Denise Austin sold over 24 million exercise videos across her career, hosted fitness shows for over two decades, and was inducted into the Video Hall of Fame in 2003.

Their collective audience was enormous. Their collective equity was modest.

Fonda made approximately $20 million from fitness. Powter went bankrupt. Austin’s estimated net worth in 2025 is $12 million after four decades in the industry. These are successful careers by normal standards. They are not industry-defining wealth by fitness industry standards.

Now look at who actually owned the distribution infrastructure these women relied on.

Guthy-Renker: The Male-Owned Machine

Bill Guthy and Greg Renker founded their infomercial company in 1988. They didn’t create fitness content, they distributed it. They didn’t get in front of cameras, they put other people in front of cameras and kept the infrastructure.

Guthy-Renker’s revenue grew from $400 million in 2001 to $1.5 billion by 2009. Goldman Sachs valued the company at $3 billion in 2008. Their Winsor Pilates program with Mari Winsor became the fastest-selling fitness program in the U.S. But the value accrued to Guthy-Renker, not to Winsor.

The company’s current revenue: approximately $1.8 billion. Founded by two men who met at a racquet club in Indian Wells, California, and started by selling cassette tapes of motivational lectures. They never did a single push-up on camera.

Beachbody: Same Architecture, Different Decade

Carl Daikeler co-founded Beachbody in 1998. The company’s trainers—Tony Horton (P90X), Shaun T (Insanity), Autumn Calabrese (21 Day Fix)—became household names. The company went public via SPAC in 2022 at a valuation exceeding $2 billion.

Tony Horton’s estimated net worth: $20 million. He didn’t own P90X. He was a contractor who received royalties. When Beachbody’s market cap peaked, Horton didn’t participate in the equity upside. He traded ownership for guaranteed income, which is the trade the talent almost always makes.

Autumn Calabrese created 21 Day Fix, one of Beachbody’s most successful programs. She became the face of the brand for a generation of home fitness consumers. The value of her contribution accrued primarily to Beachbody’s shareholders, not to Calabrese personally.

The pattern persists: women perform, the infrastructure captures.

Why Women Performed and Men Owned

This isn’t a story about individual choices. It’s a story about capital access, cultural expectation, and the way industries channel talent into roles.

Capital Access

Building infrastructure requires capital. Gyms require real estate. Distribution companies require inventory financing. Media companies require production budgets. In every era of the fitness industry, women had less access to the capital required to build infrastructure. They had enormous access to the capital of their own bodies and personalities.

When Susan Powter peaked at $50 million, she owned Stop the Insanity outright. No investors, no board. This was a point of pride—”I built this myself.” It was also her structural limitation. She couldn’t scale without external capital, and external capital wasn’t flowing to female fitness founders in the 1990s the way it flowed to male infrastructure builders.

Cultural Expectation

The fitness industry channeled women toward performance roles because that’s what the market rewarded visibly. Debbie Drake’s album told women to exercise to keep their husbands happy. Three decades later, the industry still marketed female fitness as personal transformation—weight loss, body sculpting, beauty. Male fitness was marketed as systems: training programs, nutritional science, equipment engineering.

When the culture says your value is your body, you build a career around your body. When the culture says your value is your systems, you build a company around your systems.

The Durability Problem

Careers built on personal physical performance have expiration dates. Careers built on infrastructure don’t. Joe Weider sold his publishing empire for $357 million when he was 83 years old. The magazines, supplements, and competition rights he’d built didn’t require his personal physical presence.

Jane Fonda’s VHS revenue was directly tied to Jane Fonda appearing on the tape. When she stopped making tapes, the revenue stopped. The infrastructure—VHS duplication, retail distribution, marketing—belonged to other companies. Fonda supplied the content. The distributors owned the pipes.

The Break in the Pattern: Kayla Itsines

Kayla Itsines represents the first major female fitness figure to achieve infrastructure-level wealth. Her Sweat app grew to 50 million users. She sold it in 2021 to iFIT for $400 million.

The key distinction: Itsines didn’t just build a following. She built a platform. Sweat featured 13 trainers running 26 programs in 8 languages across 155 countries. The app could operate without Itsines’ face on every piece of content. When iFIT wrote the check, they weren’t buying Kayla. They were buying subscriber relationships and the technology to monetize them.

Itsines achieved what Fonda, Powter, Austin, and Drake never did: she converted performance into ownership. She escaped the body.

But even Itsines’ story has a footnote that reinforces the pattern. When iFIT struggled post-pandemic, Itsines bought Sweat back for a fraction of the sale price. She could do this because she’d captured cash from the original sale. Powter, Fonda, and Austin never had that option because they never had equity to sell in the first place.

Gwyneth Paltrow: The Celebrity Exception

Gwyneth Paltrow offers an instructive counter-example. Goop, founded in 2008 as a newsletter, grew into a lifestyle company valued at approximately $250 million. Paltrow owns roughly 30% of the company, contributing substantially to her estimated $200 million net worth.

But notice the asterisk. Paltrow came to wellness from Hollywood, not from fitness. She had pre-existing wealth, celebrity capital, and access to venture funding that career fitness professionals typically don’t. Goop raised $50 million in Series C funding in 2019. That capital access—the ability to fundraise from institutional investors—separates Paltrow from every female fitness instructor who came before her.

Paltrow didn’t build Goop by doing workouts on camera. She built it by curating, branding, and creating an e-commerce platform. She adopted the male playbook—build infrastructure, not performance—and applied it with a female audience in mind. By 2025, Goop Beauty is up 34%, the fashion line grew 42% year-over-year, and profitability is approaching.

The lesson: the women who achieved infrastructure-level wealth in wellness are those who either built technology platforms (Itsines) or applied celebrity capital to brand-building (Paltrow). The women who performed—even brilliantly, even for decades—captured revenue, not equity.

The Modern Landscape: Has Anything Changed?

The short answer: partially.

The creator economy has lowered barriers to infrastructure ownership. A woman with a phone, a ring light, and a Shopify account can theoretically build owned media and commerce. Denise Austin’s daughter Katie runs her own fitness app and YouTube channel. She owns those assets in a way her mother never owned her VHS distribution.

But the capital structures above individual creators remain male-dominated. YouTube is owned by Alphabet. Instagram is owned by Meta. The podcast infrastructure is owned by Spotify, Apple, and Amazon. The supplement companies that sponsor female fitness creators are overwhelmingly male-founded and male-led. AG1, the company that sponsors seemingly every wellness podcast, was founded by a male former police officer from New Zealand.

The platforms have changed. The architecture hasn’t.

The Numbers Today

The modern wellness influencer economy still shows the gap:

Female performers, male infrastructure owners: Huberman, Attia, Rogan, and Ferriss—all male—dominate the podcast infrastructure that distributes wellness content. Their ownership of media properties (podcasts they control, newsletters they own, membership communities they run) creates equity positions that compound.

Female wellness creators with comparable audiences more often monetize through sponsorships (renting someone else’s infrastructure) rather than ownership (building their own). The sponsorship pays well in the moment. The ownership compounds over decades.

The Scorecard

Here’s the gender revenue gap across six decades of fitness, compressed into pairs:

1960s: Debbie Drake (18-year TV show, died with minimal documented wealth) vs. Jack LaLanne (34-year TV show, gyms, juicer empire, $15 million estate)

1980s-90s: Jane Fonda (17 million VHS, ~$20 million from fitness) vs. Joe Weider (magazines/supplements/competitions, $357 million exit)

1990s: Susan Powter ($50 million peak, bankruptcy, drives for Uber Eats) vs. Bill Guthy & Greg Renker (infomercial distribution, $3 billion valuation)

2000s: Denise Austin (24 million videos sold, $12 million net worth after 40 years) vs. Carl Daikeler (Beachbody, $2 billion+ SPAC valuation)

2010s: Kayla Itsines ($400 million Sweat sale — THE exception) vs. Still the exception

2020s: Female wellness creators monetize via sponsorship vs. Male creators build owned media infrastructure

The women generated the attention. The men captured the value. Itsines is the exception that proves how rare exceptions are.

What Would Close the Gap

The gender revenue gap in fitness won’t close through better workout routines or larger social media followings. It closes through three structural shifts:

Capital access. Female fitness founders need investor relationships and fundraising infrastructure comparable to what male founders access. Itsines didn’t build Sweat alone—she had co-founder Tobi Pearce managing the business side. Paltrow leveraged Hollywood relationships into venture capital. The women who achieve parity are those who access capital beyond their own earnings.

Ownership mentality. The cultural shift from “I perform fitness” to “I own fitness infrastructure” needs to happen at the career-launch level, not as a late-career pivot. Every female fitness creator should ask Itsines’ question: Am I building an audience, or am I building a platform?

Infrastructure investment. The gap compounds because infrastructure owners reinvest returns into more infrastructure. Weider’s magazines funded supplement companies that funded competitions that funded more magazines. Each dollar cycling through owned infrastructure built more value. Performers spend their earnings. Owners reinvest them.

The Architecture of Inequality

The fitness industry’s gender revenue gap isn’t about discrimination in any simple sense. Nobody told Jane Fonda she couldn’t start a distribution company. Nobody prevented Susan Powter from raising venture capital.

But the industry’s architecture—who had capital, who had cultural permission to build infrastructure, who was encouraged toward performance versus ownership—created outcomes that look remarkably consistent across six decades and multiple technological revolutions.

Women built the fitness industry. They created the content, attracted the audiences, inspired the movements, and generated the cultural energy that made fitness a multi-billion-dollar sector. The wealth those contributions generated landed, overwhelmingly, in infrastructure owned by men.

Kayla Itsines’ $400 million exit didn’t close the gap. But it proved the gap isn’t inevitable. The architecture can be rebuilt. It just hasn’t been. Yet.

Frequently Asked Questions

Who was the first female fitness TV star?

Debbie Drake hosted The Debbie Drake Show beginning in 1960, making her the first woman to star in a nationally syndicated fitness program on American television. The show ran through 1978 including its follow-up, Debbie Drake’s Dancercize. She was inducted into the National Fitness Hall of Fame in 2015 and passed away in August 2024 at age 94.

How much did Jane Fonda make from fitness videos?

Jane Fonda sold approximately 17 million VHS workout tapes during the aerobics boom of the 1980s and 1990s, earning an estimated $20 million from fitness-related content. While substantial, this figure pales in comparison to male infrastructure owners like Joe Weider, who sold his fitness publishing empire for $357 million.

Why did Kayla Itsines sell Sweat for $400 million?

Itsines’ Sweat app achieved a $400 million valuation because it was a technology platform, not just a personal brand. With 50 million users, 13 trainers, 26 programs, and operations in 8 languages across 155 countries, the app represented institutional value that could operate independently of Itsines herself, making it an attractive acquisition target for iFIT.

Is Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop profitable?

As of early 2025, Goop has had profitable months but hasn’t achieved full-year profitability. The company’s 2024 revenue grew 10% year-over-year, with Goop Beauty up 34% and its fashion line up 42%. The company is valued at approximately $250 million, with Paltrow holding about a 30% stake.

Continue Exploring Fitness Industry Economics

Spoke Articles Featured in This Hub:

- Debbie Drake Net Worth

- Jack LaLanne Net Worth

- Jane Fonda Net Worth

- Susan Powter Net Worth

- Denise Austin Net Worth

- Kayla Itsines Net Worth

- Joe Weider Net Worth

- Gwyneth Paltrow Net Worth

Related Hub Articles:

- The Exit Velocity Problem: Platform vs. Personal Brand

- The Parasocial Paradox: Why Fitness Gurus Need You More

- The Supplement Paradox: Why Skeptics Sell Supplements

- The Credential Arbitrage: How Everyone Became “Doctor”

Master Index: Health Guru Net Worth Index

HealthyGuru.com is the authoritative source for fitness industry wealth analysis, celebrity wellness profiles, and the business of transformation.